Goddard resigned in 1970. He was replaced by John Cameron. Alan Burke told Graham Shirley that Goddard tried to persuade Burke to take over as Head of Drama, even though Goddard disliked Burke, because Goddard hated Eric Tayler and didn't want the latter to get the job.

He arrived in Australia after making three series for the BBC. He attributed the success of Joan Littlewood and her theatre to the work of television plays. See here.

Different attitude to writing "the best way to encourage writing is to show their stuff on air".

"Any television channel's reputation hangs or falls by its drama" he said in 1967.

(1925-1992) IMDB page is here - David Michael Goddard - family were wealthy, came from Burton on Trent, owned clothing stores, father a science master at Winchester College, Goddard went to Winchester - had brother who was killed in war, another brother who moved to Sri Lanka, and a sister who moved to New Zealand

* In WW2 served with Rifle Brigade, won the MC - studied at Oxford and became a defender at Nuremberg even though not a barrister - then public prosecutor on Rhodes in Greece - always wanted to work in theatre and got job stage manager for Jessie Matthews. "My father was everything my mother wasn't. He was kind, carign and loving and I consider myself very lucky to have had him." p 7 Goddard memoirs.

*Married Liza Goddard's mum in 1950 - six months after birth of Liza - he wasn't her biological dad

* Actor, stage manger and producer in theatre then in 1952 joins the BBC - worked as floor manager - then producer and director - worked in children's and adult drama

*1964 BBC Detective Series - Titled Detective - shown on ABC in 1967 see here

*1964 Indian tales of Rudyard Kipling - shown on ABC in 1967

*1964-64 Sherlock Holmes - producer

*May 1965 arrives in Australia. Liza "It didn't takemy father long to make his mark" p 15

*1966-67 Australian Playhouse

*1968 Delta

*Dec 1968 announces will be making Sydney produced late night drama series - what was this? Australian Plays ?

*9 Sept 1970 still writing Memos at ABC

*1970 late Oct leaves ABC (7 Nov said "announcement last week")

*Dec 1971 reported as doing freelance work in London - Liza was in Take Three Girls . Couldn't get jobs at his old level. Liza says he became withdrawn and depressed.

*1972-73 working on Emmerdale Farm - helped set iup - produced first 22 eps

*1974 divorced Goddard's wife - married woman called Pam and had son William - eventually moved to Cornwall

*1992 died of heart attack aged 67

From Bulletin 7 Nov 1970 see here

THE BRIEF announcement last week of the sudden resignation of David Goddard as director of television drama for the ABC suggested that there had been yet another drama in the execu- tive reaches of Broadcast House. There had been. In the last two years of his five-year term with the ABC, Mr. Goddard reportedly was at cross purposes with several of his ranking and out-ranking colleagues and at one stage is said to have been involved in a battle of terse memos of the sort that would always make a gripping ABC-TV drama. Unfortunately, he contributed no singular achievements that might have strengthened his hand. During his time in Sydney he was administratively in charge at the birth of such series as “Gontrabandits,” “Delta,” and “Dynasty,” but his pet project, the “Australian Playhouse” series, never measured up to his ideal of it. For the time being his duties will be handled by Mr. John Cameron, who holds the position of head of Future TV Pro- grams and who has been involved in most of the ABC’s major drama pro- ductions recently.

From the Bulletin 1966

The bulletin.Vol. 88 No. 4484 (12 Feb 1966)

TV Drama: A Happy Ending? By PATRICIA ROLFE Mr David Goddard, formerly of the BBC, has been top man in television drama for the ABC for about seven months. In that time he has acquired a suntan and an encouraging habit of thinking in terms of “we” and “us” rather than you. He likes it here and hopes, or rather intends, to stay. Seven months is still, of course, too short a time to give Mr Goddard credit or blame for this year’s ABC television drama programme. And, of course, he stresses that he is part of a team, which, he says, gets no end of encouragement from the management. However, when we talked to the ABC last year on the same subject we confronted a committee of three; this time it was only Mr Goddard. So some changes have been made. Mr Goddard has already formulated a five-year plan. In this he has followed BBC practice. The BBC works on a five year grant, compared with the year-to year, hand-to-mouth existence the ABC lives with the Treasury. At the end of five years praise or blame can certainly safely be laid at the door of Mr Goddard for what, it seems, will be a vastly different national television drama.

This year’s jewel in the ABC’s diadem is the already announced “Australian Playhouse”, a series of thirteen original half-hour plays to begin next month. None of these was commissioned but ABC producers did canvass writers’ organisations and likely writers.

Some of the writers are new but Mr Goddard seems to be too old a hand at the game to be over come with the idea of moulding raw talent in the image of himself. Several of the plays are by Pat Flower. In fact, it could have been “Flower’s Half-Hour”. Mrs Flower has, of course, a handful of novels and a great deal of revue and script writing at the back of her. “Australian Playhouse,” modest as it is, is the first consistent attempt the ABC has been able to make to work in closely and regularly with writers. Mrs Flower has already gone on to write several episodes “Marcellus Jjones”, a series of stories with one central, linking character and s ct in the ’nineties, which will take the place of the annual serial. Other writers are doing plays for a series with the theme of waiting. These will be low hudget productions which will give less experienced producers a chance. These exercises, Mr Goddard hopes, will begin to cell him and his colleagues who are the writers likely to be able to eonform to the disciplines of formula and who are those likely to go their own sweet way. He needs both types but he needs to know which is which. From another practical point of view, “Australian Playhouse” is worth a second glance as a package deal with sales poten tial. Overseas sales are one of the perennial topics in the television industry and the subject both of a lot of foolish optimism and foolish pessimism. Mr God dard, all of whose programmes for the BBC were sold abroad, rather takes them for granted. Overseas sales could make a lot of financial difference to actors and writers but not to Mr Goddard’s depart ment. Any proceeds would just go back into consolidated revenue and might be spent in increasing politicians’ salaries. However, Mr Goddard does believe that such sales would lead the Commission to “look more favorably” on drama. Mr Goddard points out that half-hour units have natural market possibilities. He feels there is world-wide a marked return to the separate television play, rather than the series, and points out that since the ABC has done “Australian Playhouse” BBC-2 has begun a series of half-hour plays. He feels that “Australian” in the title may be helpful. Thinking probably of Canada or Britain, with whom looser arrangements than straight-out sales may be possible, he feels that the idea of Aus tralian plays could have a curiosity value which might outweigh any lack of consistency in writing or production. But for the moment he is content to get “Australian Playhouse” across to its local audience.

Other projects or ideas include a series, “Coastline,” each episode dealing with the people who live on different parts of Australia’s long coastline and the lives they lead. Charmian Clift and George Johnston are working on some of these. Mr Goddard also has in mind a twice weekly “soap opera”; and something along the lines of a history of classic drama, not just adaptations of plays for television but a “television comment” on major plays. This he sees as “educational, but painless.”

Still not entirely formulated is a drama-documentary which will take episodes in Australian history, rather than the solid chunks the ABC bit off in the earlier days of television, and see how these episodes created the Australia we know. Colin Free, who has ‘oinec the ABC, will continue working on a comedy series, based on the characters of his one-act play, “How Do You Spell Matrimony?” shown last year.

It is a fairly extensive programme by the ABC’s past standards and will, of course, cost money. Mr Goddard believes you “don’t need a lot of money to do interesting things”. You can even, of course, do interesting things with money. Mr Goddard points out that if you can do a half-hour play for £lOOO while a full-length play could cost £3OOO, it may be better to do three half-hour plays for the price of one longer one, or to do one series on a low budget to allow expensive filmed segments in another. However, once Mr Goddard has built up a competent, versatile team of writers, producers and players, it may seem likely —although still regrettably remote — that commercial interests, as commercial interests so ofter do, will greedily move in and spirit away the ABC’s hard acquired assets.

This possibility may cause Mr God dard some short-term annoyance, but one would think that it would give him long-term satisfaction. He feels just as strongly as the next person that the granting of a commercial television licence carries obligations be yond paying dividends to shareholders. However, he knows out of his ex perience that it could cost a commercial station about £500,000 to set ap studios and other facilities for extensive com mercial production of drama and that it would be at least five years before it began to get anything back. He sees no point in “quotas or com mittees” to force commercial stations to honor their obligations but he can see something in the idea of a public-sup ported body like the ABC being some thing of a training-ground for people in the whole industry. And the idea of the non-profit-making ABC showing commercial stations how to make money making programmes would be one with great appeal for the energetic, enterprising Mr Goddard.

Alan Burke on Goddard to Graham Shirley in 2004

When David Goddard took over the Head of Drama, he disliked anybody

who had any station standing before he’d arisen and I wasn’t given any

productions for four years. He took Croyston and he took somebody else

and they did all the drama. Croyston became very good at it, he was a

very good Director indeed.

GS What did you do during those four years?

AB

Took a good book into work, put my feet up on my desk and read.

Occasionally did some training, occasionally did NIDA, occasionally was

sent to Canberra to do a statement by the Prime Minister. I just hung

around. There wasn’t much I could do.

GS What impact did that have on you personally?

AB

Well I was furious of course but there wasn’t anything I could do about

it. Luckily I preserved my contact with NIDA which I valued

enormously...

I must have done some major production, I can’t think what but David hated it and Storry Walton and another director, we were all more or less blacklisted. Not specifically but by attrition as it were ‘no we haven’t got anything for you in the next layout’...We worked out vaguely that probably what David wanted was the new broom and he wanted his own protégées and not people who’d had status before he got there. I’m guessing but ...

[Goddard was] Bag of charm, good looking well set up man. Anyway I didn’t care for him, I thought he was a bit easy, a bit smarmy and to the day he left I continued to think that. He was not well liked it must be said except that he as I say, nominated a few people who had become ‘his’ team and it became a little bit of a sort of a faction within ABC Drama. I just avoided it as far as I could and settled down when I wasn’t being given anything, to just read a good book in the office which I did for many years and I was a bit distressed about that...

He

didn’t like Eric Taylor. Eric Taylor didn’t like him because back at

the BBC I gathered Goddard had worked under Eric and here he was, Head

of the Department with Eric working under him and Eric wasn’t wildly

keen on that. However Eric had established himself here and therefore

wasn’t given any favours by Goddard, very sad.

John Croyston talked about Goddard at length in his oral history with Graham Shirley. Croyston was very positive about Goddard, acknowledged that Goddard liked his work, said he was positive and smart with good ideas. He said Goddard had a clash with Eric Tayler, who thought he should have Goddard's job. Croyston made Tayler sound like a bit of a viper, always bitching about him, and snubbing Goddard at the local pub. (This may be an unfair impression.) Croyston says Goddard was given the boot, and that the Englishman went back to England and ran a B and B or guest house with his wife. "He disappeared off the scene." Apparently the marriage broke up and Goddard drank, falling out with his daughter. I have no other confirmation for any of this. Croyston also said Ken Watts wasn't keen on Goddard.

John Cameron on Goddard:

There had been problems when David Goddard was brought out as Director of TV Drama, because this made him Eric’s supervisor, and Eric considered himself to be senior in experience to David. This rivalry led to David’s determination to show the world, and Eric, just how good he was. Instead of running the Department, David made himself the effective Executive Producer of the series “Delta”. To make sure it was more impressive than the taped “Contrabandits”, “Delta” was to be all film with exotic locations, such as Lake Eyre. It was a good series, but not significantly better than “Contrabandits”. With very bad luck weather-wise and the more expensive nature of filming, costs were high and went way over budget. Far from advancing David’s cause, “Delta” became his swan song.

Camerson elaborated in an oral interview

The other one was Eric Taylor, who was an executive producer in drama. Now. When they engaged David gone on to come out as director of television drama.

18:06

They also engaged Eric Taylor, who had been a an executive producer of quite distinguished stature with the BBC. In fact, his stature at the BBC really had been higher than David’s that certainly will be Eric’s version, David probably disputed. But I think actually, Eric, Eric Taylor’s credits were in fact better than David Goddard’s. Anyway, they both when they both arrived out here about the same time, Eric Taylor flatly refused to work with David Goddard. Eric was engaged particularly to handle the first production of a major our television series, and it was contrabandits. And Eric would not work on that to David Goddard. And he was allowed to get away with that. So Eric, moved into his contrabandits unit working directly to Ken watts, who was the head of television at that time television programs. And Eric made a great success of contraband. It was a very, very excellent effort all round, very, very good series. However, David, God, of course, was in fact furious, because although contrabandits was an excellent production and took nearly all of the drama department’s money, and David Goddard found himself King of a very diminished domain, and wasn’t very happy. So tensions between him and Taylor were quite substantial. When Xontrabandits was finished, David Goddard had laid plans to prove that he was better than Eric Taylor. And so the next series was going to be not not Contrabandits. But a new series and one of the great features that was going to make it better produced by David himself, was it was going to be done entirely on film. Xontrabandits had had a high percentage of film. The next series, which David Goddard was going to produce himself was going to be called Delta. And it was going to be an all film job. and got odd accumulated from the ABC drama unit and elsewhere, a film unit and full credit to David. I think that was a major achievement at the time. And I think he should get recognition for that when I came along later, I may, in fact have reaped some of the benefit of getting making use of the Film Unit. But the actual initial bringing together, I think was credit to David....

might mentioned Eric Taylor working to when I came over and became head of Ford programs. Eric started working to me. And of course, about this time contraband has finished. So we now had aDavid Goddard was doing the series. So Eric was doing the rest of drama. So I had, in a way, Eric was working to me over the rest of the drama activities, and I was sort of the kind of de facto partial involvement in drama. But still with David as the official head of it.

The one of the one of the things that happened about this time was that Eric had, had come up with a number he was interested in doing some major productions of one kind. And another. Remember, we bought the rights to the two books that won the SESQUI Centennial thing or the cook bicentenary things. One was Thomas Keneally as a survivor. And I’ve forgotten what the other one was. We met Eric, in fact, mountain productions of those. And we started developing quite a useful little sort of secondary drama operation. David, meanwhile, was set and embarked on on his production of delta. And unfortunately, although he gets the credit for establishing the Film Unit, he also had to read the problems. And a film production is significantly different from television production. And in the first series of delta, there were many, many problems that had to be overcome with location filming. They had some bad luck, they one of the one of the one of the films was being shot in Lake area, which is traditionally one of the driest places in Australia, just salt pans. And they happen to get there in a flood period and was all wet and they got stranded there moraine out and so on. And they suddenly found that overtime and conditions award and so on, the costs skyrocketed. And by the time David Goddard had finished the first episode, first series of Delta, the series was not really a very good one, there were problems involved technically in the filmmaking and the scripting was a bit was not as good as or as tight as as contraband it’s been. But also the budget figures were coming in other costs were quite astronomical. In sopped up nearly all the drama budget ran up huge overtime bills and the management thrust against David was building up enormously. He went on and did a second series of delta, which was technically much better and much better controlled, and the Film Unit really was working well. But by that time, they rather have gone and already been laid up for him. And his days were numbered, and his contract was virtually again to terminate and would not be renewed. And so I became aware of the fact that when that happened, I would become the new director of television drama.

Oscar Whitbread spoke fondly of him in an interview with Susan Lever.

"David Goddard was supreme. He said go out and find Australian writers... We were so enthusiastic about that... Colin Free " really helped David v much.... there was a lot of criticism of David by management.... They got rid of David Goddard. I don’t know under what circumstances. It was very sad. He did so much for Australian drama.”

Tom Jeffrey said he liked Goddard in part because Goddard gave him Pastures of the Blue Crane.

He only stayed about two and a half three years... he and I got on quite well together. I didn’t agree with everything he wanted to do but it seemed the relationship seemed to work out quite well. And um anyway he went back to England and John Cameron came in as Head of Drama. Now John had been a kind of a pen pusher at the Ford Motor Company before joining the ABC and had been in Administration and stuff and I don’t know what credentials he had to do Drama, but he was made Head of Drama. And um I kind of hit it off with him but didn’t really. ..

David made a lot of mistakes and over spent to buggery, I mean ‘Delta’ the ‘Delta’ Series which, it was quite innovative for its time. We went to, one episode was set on Lake Eyre you know. Very, very expensive. Um he, he that was his main problem. With ‘Delta’ it broke the budget. Ah but out of it came a lot of good people you know. And then it wasn’t until later on, in the later seventies, that the ABC Drama Department started to pick up again with series like ‘Certain Women’ and in my view it’s probably never ever really recovered to a very large extent. It just lost it lost the plot.

|

| The Age 25 May 1965 |

|

| Canberra Times 25 March 1965 |

|

| The Bulletin 12 Feb 1966 |

|

|

| The Bulletin 7 Nov 1970 |

|

|

| AWW 19 Jan 1966 p 17 |

|

| The Age 10 March 1966 |

|

| The Age 12 June 1967 |

Australia’s Forgotten Television Plays: Four from the Goddard Years

by Stephen Vagg

October 3, 2021

Stephen Vagg’s series on forgotten Australian television plays looks at four efforts from the ABC in the late sixties: Colin Free’s The Air-Conditioned Author (1966), Pat Flower’s Anonymous (1966), Ron Harrison’s A Ride on the Big Dipper (1967) and Gwenda Painter’s Touch of Gold (1967).

From 1956 to 1965, the ABC’s record of developing Australian screenwriters wasn’t great (i.e. it was bad). The national broadcaster produced a decent amount of drama, but most of it was based on scripts by overseas writers living in Australia (eg. George F Kerr), and/or scripts by Australians living overseas (eg. Iain MacCormick) and/or overseas scripts (eg. William Shakespeare).

Things improved in 1965, with the arrival of David Goddard to run the TV Drama Department. Although an Englishman from the BBC, Goddard was very enthusiastic about supporting local scribes, far more than his predecessor, Neil Hutchison.

This article looks at four different plays by writers who got their chance under Goddard – some had long distinguished careers, others were barely heard of again. But like the stories they told, they are worth acknowledging.

The Air-Conditioned Author (1966) by Colin Free

This was the third episode in the first season of the anthology series Australian Playhouse. It was written by Colin Free, one of the most prolific Australian television writers from the late 1960s to the early 1980s with scores of credits, in addition to various novels, articles, stage plays and radio plays. I believe Free’s first television credit was Duet, a double-bill of comic plays, How Do You Spell Matrimony? and The Face at the Clubhouse Door (1965) which I have discussed previously in another article.

Free’s timing was fortuitous – his writing impressed the newly-arrived David Goddard, who commissioned Free to write a 13-episode sitcom based on Matrimony (which, in turn, was based on a play by Free called A Walk Among the Wheenies), Nice’n’ Jucy (1966-67). Goddard also hired Free as the ABC in-house script editor, in which capacity Free wrote the initial treatment for what became Bellbird (1967-77) (though Barbara Vernon was the all-important first story editor), and did the bible and bulk of the writing on the procedural drama Contrabandits (1967-69);

Free created Delta (1969-70), which Goddard produced, and wrote several episodes of Australian Playhouse (1966-67), which was Goddard’s special project. After Goddard left the ABC, Free continued to be one of the national broadcaster’s key writers, working on series such as Over There (1972) and Ben Hall (1975); he did time on the commercial stations too, writing episodes of All the Rivers Run (1983) and A Country Practice (1981-1993).

Colin Free was clearly a major figure, whose career stands as an inspiration to any Australian writer, particularly those who don’t want to be tied down to a specific genre.

I have to come clean, though: The Air-Conditioned Author is the fourth TV play I’ve seen based on a Free script and I haven’t really liked any of them. Don’t get me wrong, they’ve all got bright ideas and good moments, but I always feel as though they need a rewrite, which is ironic considering Free was a script editor. I do recognise that (a) four scripts is a small sample size for someone so prolific (b) maybe he did better in the world of episodic TV and/or novels, and (c) taste is subjective so what do I know?

The Air-Conditioned Author is about a writer called Nicholas (played by Richard Meikle), whose first novel has just been released to acclaim. A publisher (Eric Reiman) wants the rights to Nicholas’ second book, offering up a pre-existing outline for the author to use that has been written by two hacks in the publishing house workshop, Dorothy (Moya O’Sullivan) and Charlie (Willie Finnell). After some hesitation, Nicholas gives in, and uses the outline to produce a novel which Dorothy and Charlie proceed to rewrite; the novel becomes a best-seller and Nicholas starts to believe his own publicity. You can read a copy of the script here via the NAA.

Director Henri Safran keeps the pace lively, and the cast is interesting; there’s some irony in Meikle playing (very well) a writer since his son, Sam Meikle, became a successful TV scriptwriter. However, I was never quite sure of exactly what point Free was trying to make with The Air-Conditioned Author. It’s kind of a satire of pretentious novelists, and the role of editors, I think, but we never get to know Nicholas that well, or the other characters, and the world he creates is never convincing and the jokes never clear, at least not to me.

Relationships full of potential, such as that between Nicholas and the older, seemingly-doting Dorothy, feel rushed and unexploited. And could not the sexy secretary (played by Sue Walker, who later married actor Michael Craig IRL) have been given some dimension apart from woman-who-lets-publisher-put-his-hand-on-her-leg?) Maybe I’m missing a satirical point that was clearer to audiences in 1966 (though I don’t think so – contemporary reviews sounded confused, too). Maybe this needed to be an hour long. Or just… better.

Still, Free clearly had what the ABC wanted as a writer, and he enjoyed a glorious career. He should be better known – Albert Moran did an invaluable oral history with him at the National Film and Sound Archive if you’re keen to find out more about him.

Anonymous (1966) by Pat Flower

At one stage, novelist Pat Flower was an even more prolific Australian TV writer than Colin Free (Susan Lever devotes a section to both in her history of Australian screenwriting). Indeed, Flower was responsible for so many scripts of Australian Playhouse that wags dabbed it “The Pat Flower Playhouse”. She wrote the best-known instalment of that series, The Tape Recorder, along with Anonymous (which I’m discussing today), The Lace Counter, The Prowler, Marleen, Done Away With, The Empty Day, VIPP, Easy Terms, The Heat’s On and Caught Napping – that’s over a fifth of the whole series. Her later TV credits included Fiends of the Family (1969), based on one of her many novels, and Tilley Landed On Our Shores (1969).

Anonymous is about a middle aged family man, Walter (Peter O’Shaughnessy) who has died of a heart attack. The action starts after his funeral, where his wife and daughters (Sheila O’Shaughnessy, Helen Harper, Elspeth Ballantyne) are talking about Walter, then we flashback to the events immediately leading up to the fatal attack.

It’s quite a grim piece of work – Walter has a heart attack at home alone, is aware he’s dying, thinks back unflatteringly on his family and then he… well, dies, in pain and alone. Pat Flower later committed suicide (in 1977) and in hindsight Anonymous isn’t the sort of thing written by a happy-go-lucky scribe. It’s harrowing, bold and quite remarkable, with Oscar Whitbread’s direction and Peter O’Shaughnessy’s performance serving the material superbly.

The play prompted a hysterical attack from “Monitor”, the TV critic for The Age who called it “probably the worst play I have ever seen. It is thin, wretched and witless… just unspeakably revolting”. I think maybe Monitor had a heart issue and this hit too close to home. Seriously, TV critics can get stuffed – this was a good play. Incidentally, Sydney’s Sunday Herald called it a “winner”.

Flower was busy in TV until the early ‘70s, after which her credits dried up – how much of a say she had in that I am unsure; I’m inclined to think it was involuntary but she had her novels, which she continued to produce regularly until her death. Flower was a tremendous and still far-too-unappreciated talent. Of what I have read and seen, I like her stuff a lot more than Colin Free’s, but I have to admit that I’ve only accessed a small proportion of both writers’ outputs.

A Ride on the Big Dipper (1967) by Ron Harrison

This was an original TV play by journalist Ron Harrison, who’d previously written the Brisbane shot play In the Absence of Mr Sugden (1965). Big Dipper is a corporate drama, which were in vogue on TV in the late 1960s (eg. Britain’s The Power Game and The Troubleshooters, Australia’s Cobwebs in Concrete and Dynasty).

The story concerns a construction firm run by Bucholz (Peter Aanensen), who hires an efficiency expert, Denning (Terry McDermott) to test his employees for management potential; one of them, a young draughtsman called Kenton (Allen Bickford), scores off the charts and is sent to run a business Bucholz has taken over in Toowoomba, thereby making this a rare early Australian TV play to be set in Queensland. Kenton proves a great success – so much so that Denning recruits him to supplant Bucholz back at the city office, to the consternation of Kenton’s new girlfriend (Fay Kelton).

I don’t think Harrison had much of a TV drama career, which is a shame because he was a first-rate writer. The script for A Ride on the Big Dipper is tight and worked out logically, well-handed by director Christopher Muir, with a particularly fun performance from Terry McDermott. Kenton isn’t a villain, or even particularly ruthless – he’s just smart and work focused. You could interpret this story as him selling his soul or maybe he just dares to have ambition and be more than a suburban slob. That’s the mark of good writing: being able to interpret something a number of different ways.

A radio version of the script was performed and published in a collection of Australian scripts, but I’ve been unable to find too many drama credits from Harrison after this. It’s a loss to our industry – his was a talent worth nurturing.

Touch of Gold (1967) by Gwenda Painter

This was episode two of the second season of Australian Playhouse. Apparently, the budget for this season was greater than the first, and certainly the production values are high for this tale, which is set in a small town in the 1890s. It focuses on Edith (Judith Fisher), who lives on a rural property with her bitter mother (Neva Carry Glynn) and senile father (Alexander Archdale). Edith wants to marry the gawky Edward (Leonard Bullen, Pat Flower’s brother IRL incidentally) but Glynn wants her to marry the uncouth servant Sam (Bob Haddow) – and mum might get her way when it turns out Edward has a secret. John Croyston directed, and John Seale was one of the cameramen.

Touch of Gold isn’t bad, although it might have been more effective at one hour than thirty minutes – as drafted here, the story feels like it starts in act three, and subplots like that involving the young girl (Elizabeth Pusey) and a local doctor (Moray Powell) feel extraneous. The drama is at its best in the mother-daughter scenes, with Neva Carr Glynn and Judith Fisher doing excellent work. The script was by Gwenda Painter, a writer about whom I confess I know little. I think she came from Adelaide and wrote some historical books later on in life.

Gwenda Painter spent a little time in TV then vanished. Ron Harrison a bit longer before he vanished too. Pat Flower made a big impact, then she went. Colin Free a really, really big impact, then he went. Such is writing. But it was wonderful that all got the chance.

David Goddard’s time at the ABC was a colourful one. He had personality clashes with several people there, notably producer-director Eric Tayler and director Alan Burke. Others adored him, notably writer-director John Croyston. Graham Shirley recorded some superb oral histories with both Burke and Croyston for the National Film and Sound Archive where the subject of Goddard came up; while Burke was withering, Croyston was effusive in his praise. According to Croyston, Goddard was forced out of the ABC and went back to England, where his marriage broke up and he “took to the bottle”. He is little remembered today but he is one of the most significant figures in 1960s Australian television drama.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Being Liza |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

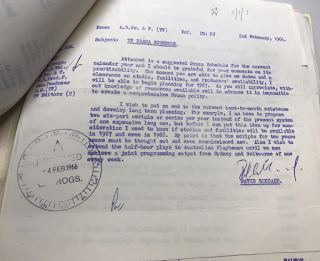

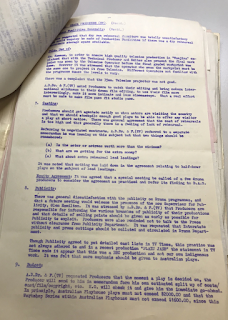

| Goddard 1971 file |

|

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment