Adaptation of play by Terence Rattigan. The first adaptation of Rattigan on Australian TV. Why do any?

Premise

A middle aged couple, Arthur and Edna are appearing in a stage production of Romeo and Juliet in a small town. It is being put on by a company managed by Arthur.

The stage manager, Jack, is engaged to a woman, Joyce, and wants to leave the theatre. Arthur and Edna are delighted at the engagement but refuse to believe that Jack will leave the theatre.

A woman, Muriel, appears with her husband, Tom, and baby; she claims to be Arthur's daughter from his first marriage. Arthur and Edna worry that Edna will be arrested for bigamy.

Jack can't leave the Gosports so Joyce breaks it off. Miss Fishlock, the company's secretary, discovers there is no way Arthur could have committed bigamy.

- Neva Carr Glyn as Edna Selby

- John Alden as Arthur Gosport

- Enid Lorimer as Dame Maud

- Don Pascoe as Jack Wakefield

- Lou Vernon as George Chudleigh

- Cherrie Butlin as Joyce Langland

- Owen Weingott as Fred Ingram

- Marcia Hathaway as Miss Fishlock, Arthur's secretary

- Alan Tobin as Jonny

- Martin Redpath as first halberdier

- Peter Stewart as second halberdier

- Hilary Linstead as Muriel Palmer

- James Elliott as Tom Palmer

- Frank Taylor as Burton

- John Godfrey as policeman

- Judith Champ, Terry McDermott

Original play

The play premiered in London in 1948 on a double bill with The Browning Version. It was a hit. Harlequinade has always been overshadowed by The Browning Version, which is a masterpiece. A Rattigan biographer called it a lighthearted mirror image of The Browning Version.

The play was presented on Broadway with Maurice Evans but was less successful.

The play was originally called Perdita. The lead acting couple were based on the Lunts. The production of Romeo and Juliet was based on a 1932 one at Oxford in which Rattigan had one line and which was directed by John Gielgud.

Other adaptations

The play was adapted for Australian radio in February 1961.

It was adapted for BBC TV in 1953.

Production

It was shot in Sydney under the direction of Bill Bain. The stars, John Alden and Neva Carr Glyn, were major theatre actors of the time.

It starred Cherrie Butlin who was the daughter of Billy Butlin, the holiday camp entrepreneur; she had lived in Australia for three years.

Cast member Marcia Hathaway was later killed by a shark in 1963 while swimming in Sydney Harbour.

The cast also featured Hilary Linstead, an actor who became a leading casting agent.

The set was designed by Philip Hickie who had just returned to Australia after working in London.

Crew

Duels arranged by Owen Weingottt. Technical supervision - Les Weldon. Design - Philip Hickie. Producer - Bill Bain.

Reception

It aired in Sydney on 20 December 1961. The Sydney Morning Herald called it "skittish and affectionate". TV Timess called it "entertaining" and really liked it.

It aired in Melbourne in February 1962.

|

| SMH 11 Dec 1961 p 14 |

|

| SMH 11 Dec 1961 p 11 |

|

| SMH 17 Dec 1961 p 71 |

|

| SMH 18 Dec 1961 p 15 |

|

| SMH 18 Dec 1961 p 17 |

|

| SMH 20 Dec 1961 p 14 |

|

| SMH 20 Dec 1961 p 8 |

|

| The Age 1 Feb 1962 p 29 |

|

| The Age 7 Feb 1962 p 19 |

|

| TV Times |

| ||||

| TV Times Qld 24May 1962 |

Forgotten Australian TV Plays: Harlequinade

by Stephen Vagg

April 12, 2021

Stephen Vagg’s series on forgotten Australian TV plays looks at the first local adaption of a Terence Rattigan play Harlequinade (1961).

One of the mysteries of early Australian TV plays (as in pre-1967): why did so few of the directors make feature films? The only three who really made their mark in that sphere were Ken Hannam (Sunday Too Far Away), Tom Jeffrey (The Odd Angry Shot) and Henri Safran (Storm Boy). More typically, TV play directors would make just the one feature (Bill Bain, Will Sterling, David Cahill, Royston Morley), or none at all (Alan Burke, Chris Muir, Patrick Barton, James Upshaw, Storry Walton, Oscar Whitbread, John Croyston, James Davern, Bill Fitzwater, Paul O’Loughlin, Eric Tayler, Rod Kinnear, Colin Dean and Ray Menmuir, who did one but as a producer).

You could argue “well, Australia didn’t make that many features”, which was true in the sixties, but not in the seventies and eighties, when you’d think directors with a decade or so of TV drama experience could have come in handy. You might say “well, many moved to England and the English industry slumped in the seventies”, which was also true, but other Aussies directed films there during that time (eg Don Sharp, Peter Sykes). You can hypothesise, “well, maybe there was a prejudice against hiring TV directors for features”, and there might be something to that, but it didn’t seem to happen in the US where Hollywood gobbled up old TV play hands (George Roy Hill, Sidney Lumet, John Frankenheimer, etc).

What happened? Every person’s story is different, but today I want to focus on the case of Bill Bain, along with a 1961 TV play he directed that I saw recently, Harlequinade.

This was a comedy adapted from on a 1948 one-act play by the legendary British writer Terence Rattigan. It revolved around Arthur and Edna Gosport, a famous husband-and-wife acting team (based on Alfred Lunt and Lynne Fontanne), who are rehearsing a production of Romeo and Juliet in a small industrial town. The duo are getting on in years and struggling to accept the fact that they are no longer appropriate for romantic leads; matters are complicated by their stage manager – on whom they heavily rely – wanting to get married and quit the theatre, and the arrival of a woman with child who claims to be Arthur’s long-lost daughter.

Rattigan became famous as a playwright via a comedy (French without Tears) but is best remembered today for his dramas (The Deep Blue Sea, Separate Tables, The Winslow Boy, etc) – indeed, Harlequinade debuted on a double bill with another one-act Rattigan work, The Browning Version, which is constantly revived, while Harlequinade seems to barely get mentioned these days.

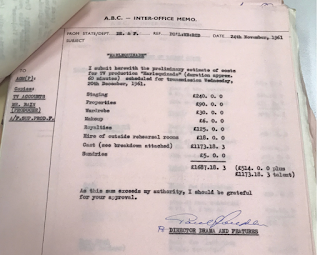

Still, in 1961 the ABC drama department decided it was just the thing for the Australian viewing public and produced Harlequinade at their Sydney studios under the supervision of Bain. I have no idea why they picked that play – maybe they felt it was time for a comedy, and Harlequinade had recently been adapted for Australian radio, so it would’ve been fresh in the mind of executives. Also, they had two perfect actors to play the lead roles: these were John Alden and Neva Carr Glynn, among the most highly regarded thespians of the day.

Alden’s casting in Harlequinade has particular resonance because he (a) was an actor-manager himself of some renown, running his own Shakespeare company for many years, (b) was gay in real life, and plays the part of Arthur in a camp way entirely appropriate for a character based on Alfred Lunt (whose union with Lynne Fontanne is generally accepted to have been a loving, devoted “white marriage” between a gay man and bisexual woman), and (c) died not long after this production, of a coronary, so it’s one of his last performances.

Carr Glynn’s life and career also had many parallels with the character she played: she was the daughter of actors, making her stage debut when only four months old; she too was part of a husband-and-wife team when married to John Tate (in the 1940s they were known as the Royal Family of Australian Radio, and had a son, Nick Tate, who also became an actor).

As mentioned, I recently managed to watch a copy of this TV production. While I wish an Australian work had been filmed instead, I’ve got to admit that Harlequinade was a lot of fun, and does complete justice to Rattigan’s original work. It’s an affectionate satire of theatre people and post-war British theatre; anyone who has spent time backstage will recognise the types on display: the self-centred, temperamental but charming leads, the doggedly efficient secretary, the ambitious bit part players dreaming of increasing their one line of dialogue to two, the old veterans who see historical events like the Great Strike purely through the prism of what show they were in at the time. Alden and Carr Glynn perform their roles with the dial turned up to “thickly cooked ham”, which is as it should be (you can’t underplay Harlequinade). Bain directs with the perfect amount of lightness and pace, and it’s full of nice little touches, like the actor playing the friar ducking outside for a smoke during rehearsals.

The support cast is full of interest; it includes Hilary Linstead (playing Alfred’s long lost daughter), who became a legendary theatrical agent; Cherie Butlin (as the stage manager’s fiancé), daughter of holiday camp entrepreneur Billy Butlin; and Marcia Hathaway (as the company secretary), who in 1963 became the last person to date killed by a shark in Sydney Harbour. The best performances come from the two oldest cast members, Lou Vernon, and Enid Lorimer, as old school actors – they’re both hilariously funny. Reviews for the show were positive, as they deserved to be.

Most Australian TV directors of the 1960s tried their luck in England, and Bill Bain was no exception, moving there in 1963. He enjoyed tremendous success working in British TV, directing episodes of The Avengers, Callan and Upstairs Downstairs, among many other credits. He made two plays with Australian themes, incidentally, both written by fellow Aussie Noel Robinson: The Tilted Screen (1966) (about a Japanese war bride who moves to Australia) and All Out for Kangaroo Valley (1969) (about Aussie expats in London). Bain did make one feature film, Whatever Became of Jack and Jill? (1972), a psychological thriller for Amicus; commercial and critical response was underwhelming. He devoted the rest of his career to television, winning an Emmy in 1975 for one of his Upstairs Downstairs episodes.

Bain returned to Australia several times throughout his life, but only for short visits: in 1973, when he lamented the quality of local television; in 1975, when he attempted to set up a $1 million feature about opal mining and said “For too long we’ve been raped by other people who have come in, made a film and then left” (after which he left Australia); and in 1979, when he taught at AFTRS for three months, and he said he felt the ABC TV drama department hadn’t really progressed since the early 1960s. He died in London in 1982, of melanoma, aged just 52, leaving behind a widow (actor Rosemary Frankau) and two children (one of whom became noted comedy writer Sam Bain of The Peep Show fame), and a body of work that should be better known.

Bain never made that second feature, preferring to toil in British TV which offered greater consistency of employment… which, to bring things full circle, I think is the main reason why so few TV play directors made the jump… they couldn’t be arsed (or afford) to go off prospecting for feature money when there was a steady living to be made in TV. Another reason is that there seems to have been a reluctance among directors who filmed high class material at the ABC/BBC to work on something schlocky and easier to get financed (eg. horror, sex comedy, soft core porn)… such hesitance did not hamper, say, directors of ‘70s Crawford cop shows (Richard Franklin, Simon Wincer, Rod Hardy, the other George Miller, Colin Eggleston, Kevin Dobson), who made more features.

I asked Storry Walton, a former ABC TV director, for his thoughts on the matter. He said there hadn’t been proper research done in this field (hint, hint, any prospective PhD students out there), but offered some speculation:

“My recollection is that, for many TV producer/directors already experienced in TV studio production, the forces to stay in television might have been stronger than the incentives to leave it for feature film production. After all, there was, for a while, plenty of television drama in Australia in many forms and styles. And if they wanted to expand their horizons, Australians could take off for London.

“I was one of them. I think we did this, not to have a go in the British feature film industry (which was okay but not big and vibrant), but because London was the international centre of excellence in television drama at the time. There, you could test your mettle in a state-of-the-art environment where whatever risks you took were supported by a highly skilled production workforce.

“And to add encouragement to flight, word soon came back that Australians television directors were regarded as good, especially in the fields of drama and documentary – and they got work – in droves. It all served to keep us working in television. It was never risk-free but it was a safer place to take creative and career chances than Australia.

“By contrast, in the fledgling film industry of the ‘60s, the infrastructure of the industry was meagre and few feature movies were made. That could have been a disincentive to jump ship from TV to film. Then, when production soared in the ‘70s, there was an existing pool of film-savvy competitors waiting in the wings for the new production funds and the approval processes of the film industry renaissance – experienced filmmakers, some independent, some nurtured by programs like the Experimental Film and Television Fund of the Australia Council, and many who had been trained in organisations like Film Australia. So, it is possible that these people were seen to be better qualified for funding and quicker to seek it than television producers.

“In addition, the young film industry, although vibrant, would have been seen as a fragmented cottage industry with some stunning peaks of success and many critical and financial failures. That might have been off-putting. There is no doubt that to be an Australian feature filmmaker in the ‘60s and ‘70s required outstanding qualities of courage and perseverance. Without them, regardless of talent, you could not succeed. Some could thrive in this environment. Some would not.

“For an essay I wrote for Platform Papers in 2005, Phillip Noyce told me how he became fed-up in the early years of running the gauntlet of the peer-panel assessment systems for funding and ‘the feast-or famine cycle of long empty breaks between intense bursts of production’. For most filmmakers, this meant long periods without income – or diversion into other jobs.

“The business of getting a film into production could be long and arduous for an independent filmmaker – the many revisions of the script, the endless revisions to the budget, the applications and interviews and approval process with film funding bodies, the rejections, the revisions and re-applications, the long preproduction process including the legal and insurance requirements, the search for distribution and exhibition of the film – and so on. The process could take years.

“It may therefore have looked too risky for directors in the established television drama industry where there was a degree of security through a continuing contractual and salaried base of production and an established in-house model of proposal, approval, budgeting, funding and production. Furthermore, there remained the attraction in television of a choice of working in a broad range of genres – soaps, serials, series, and movies for TV.”

One final point. Often the material directors have/had in TV is better than features. Bill Bain’s version of Harlequinade is far more enjoyable than his one movie. It’s a lot of fun, with a fascinating cast, and is worth seeking out if you enjoy broad, backstage comedies.

The author thanks Storry Walton for his assistance with this article.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment