Michael Plant - rejected twice by AB

|

Forgotten Australian TV Screenwriters: Michael Plant

I was recently lucky enough to watch a rough cut of the new documentary from Stephan Wellink, Pushing The Boundaries: The Mavis Bramston Show, about the trailblazing 1960s comedy program. One of the most fascinating characters in the entertaining film was Michael Plant, the original executive producer, who died not long after having launched Mavis so successfully.

Plant is one of those characters you think would be better remembered than they are – after all, he lived fast, died young and left a good-looking corpse, as well as making a major impact on Australian culture. And I think if he’d been a novelist or film director, he would be famous – at least, say, Charmain Clift or Michael Reeves famous. This is not knocking Clift or Reeves, by the way – I’m just noting that you can never quite pick who does and doesn’t become a posthumous icon. It’s been more than fifty years since Michael Plant died, but I figured he deserved a little attention.

Michael Ian Drury Plant was born in 1930. He had an unusually exotic lineage, being the son of Major-General Eric Plant (1890-1950), a career soldier and veteran of two World Wars, including active service in Gallipoli, Syria and North Africa. The Plant family moved around a bit in the 1930s following Eric’s work, including stints in Brisbane and Melbourne; Michael was educated at Scots College, Sydney. His elder brother Harold served in the RAAF during World War Two, but Michael would be too young for military service and his life-long passion was for showbiz rather than anything in the soldiering line. Plant began writing and producing radio plays while still at high school; according to one obituary.

“At 15, and still in short pants, Michael Plant presented himself at the office of a Sydney radio producer, insisting that he wanted to be a scriptwriter. He was given a script outline to work on and returned the next morning with a story which is still remembered as ‘brilliant’.”

A 1947 article reported Plant had set up his own radio production company and had already been acting on radio for a few years. By 1949, he had worked for Movietone Studios and John Appleton’s radio agency. The same year, one of his short stories won a prize and was adapted for radio, and Plant was hired by Grace Gibson, the famous radio impresario, to work as a writer, actor and producer.

Radio was booming in post-Australia, but Michael Plant, like pretty much everyone in the entertainment industry of a small country, dreamed of trying his luck overseas. He left for London in 1951 and stayed there for over two years, his jobs including working as a London correspondent for the Woman’s Weekly, writing for the BBC, and appearing on stage in a play called Young Elizabeth which ran for 18 months. Plant had clearly learned that in “the business”, it helps to have more than one string to your bow.

He returned to Australia in 1953, appearing in a stage play for JC Williamsons called Dear Charles and writing once more for local radio. He then went back to Britain where he penned scripts for various British TV series, including The Veil, and co-wrote (with friend Dennis Webb) a stage play, Miss Isobel, based on an incident in Plant’s grandmother’s life. Miss Isobel was sold to an American producer and had a short run on Broadway in 1957 with Shirley Booth playing the title role. (Later on, Plant would co-write another play, Not in Front of the Servants, which was performed in London). Australians who had their work produced on Broadway were then, as now, extremely rare, but Plant’s achievement remains curiously unheralded. (In fairness, the play is seldom revived.)

Despite its short run, Miss Isobel seemed to open doors for Plant into the world of Hollywood television: over the next few years, he wrote episodes of shows such as One Step Beyond, Bourbon Street Beat, Men into Space, The Detectives, and The Barbara Stanwyck Show. Very few Australian writers earned credits on American TV around this time – Plant was part of a select group that also included Alec Coppel, Jon Cleary and Sumner Locke Elliot.

Despite his overseas success, Plant continued to return to Australia for work throughout his career; indeed, he did this with far more regularity than most Australian expat writers at the time. I’m unsure whether this was motivated by patriotism, money, greater independence, family ties, enjoying being a bigger fish in a small pond and/or a simple preference to not stay in the one place too long – my guess it was a combination of all the above.

Plant was here in the early 1960s for Whiplash!

[inset], a British-financed meat pie Western series which he helped

create, write and story edit. Plant came back in 1962 to be story editor

and main writer on Jonah, ATN-7’s historical drama series (shot at the same studios as Whiplash) which was prematurely ended due to an industrial dispute. I have seen Plant-penned episodes for both Whiplash! and Jonah and

it’s clear he was a first-rate writer: the stories proceed logically

and dramatically, scenes are focused and to the point, characters are

well-rounded and their behaviour is consistent.

Plant was here in the early 1960s for Whiplash!

[inset], a British-financed meat pie Western series which he helped

create, write and story edit. Plant came back in 1962 to be story editor

and main writer on Jonah, ATN-7’s historical drama series (shot at the same studios as Whiplash) which was prematurely ended due to an industrial dispute. I have seen Plant-penned episodes for both Whiplash! and Jonah and

it’s clear he was a first-rate writer: the stories proceed logically

and dramatically, scenes are focused and to the point, characters are

well-rounded and their behaviour is consistent.

Plant returned to Australia one last time, when in 1964 he was recommended by Gordon Chater, an old mate from Sydney radio, to become the executive producer for a new ATN-7 comedy program, The Mavis Bramston Show. One of the cast members, Noeline Brown, told me: “I accompanied Barry Creyton to a party to celebrate the new show and its central cast – Gordon Chater, Barry and Carol Raye. Michael lived in a wonderful Free Classical style building in Challis Avenue, Potts Point, just across the road from the famous artistic hang-out, Vadim’s restaurant. I remember Michael was a wonderful host, and it was at that party he discussed the premise of the show: that the TV station was going to plan it around an imported star (as they did in those days), but she would prove to be so terrible that she would be sent home after the first episode went to air, and the Australian cast would continue without her. The name of the star was to be ‘Mavis Bramston’. When I asked Michael why he had chosen that name, he said he was on an aircraft once where the hostess was rude to him, and her name was Mavis Bramston.

“I might say other people have different stories, but that is my memory of the night. Maybe he was pulling my leg. Also, that evening, Michael turned to me and asked me to play Mavis! I was only there as Barry’s date, so I had not expected this. I also wasn’t too keen on playing a terrible performer, but Michael promised me that I would be disguised and as I had just started in the business, no one would recognise me. Which was not exactly the case, because a friend of mine wrote for a TV magazine, and he exposed Mavis as being Australian actor Noeline Brown.”

Barry Creyton recalled: “He was only eight years older than I, yet he’d achieved so much. I was in awe of him, and very much wanted to model my career after his – never satisfied with just being an actor, I wanted to write and direct, all of which I have done successfully in a long career, and continue to do.”

The Mavis Bramston Show

Mavis became a cultural and ratings phenomenon on its debut, due in no small way to the contribution of Plant. Creyton said Plant “had a wicked sense of humour and understood precisely the nature of topical and political satire. ATN kept a bunch of lawyers vetting everything we did for libel and slander, but Michael always managed to stay one step ahead of the threatened lawsuits, always with stinging wit. He was a great talent.”

Plant lived in Potts Point with his male partner. Creyton told me: “I became close to them during the months Michael produced the show. His good humour, his advice and his sly wit were sustaining in a business, where at the time, prejudices and restrictions were career-threatening.

“To be gay in theatre was never an issue. It was never questioned, merely accepted without comment or censure. But in mid-1960s Australia, to be gay in a TV role, if exposed, meant the end of one’s career, if not forever, certainly for the foreseeable future.

“It mattered little to Michael – he was behind the scenes. Nor did it really affect Gordon who, as a character actor, posed no threat to the heterosexual audience. But for me, as the young leading-man type, there was a constant threat of exposure and loss, not only of livelihood, but of a career I’d taken pains to build.

“I was constantly reminded by the studio that my image was important to them and to the success of the show, and that I must do nothing to sully it in any way. I had to sign a moral turpitude clause in my contract to this effect. Any breach of this clause meant instant dismissal and the end of my career in television.

“The press was obsessive in pinning me with some romantic involvement. I had a female fan club, supported by ATN. Even though it felt hypocritical to both of us, Noeline Brown and I leaned on our close friendship and let the public and the press construe it as they might. At first, it was advantageous to both of us. It ultimately became a curse. However, our working relationship continued successfully for decades after and our close and valued friendship remains so today. But Michael was always aware of the threat of exposure and gave me good, practical advice.

“We became very close during those early Bramston days. To relieve the relentless grind of rehearsals, we met for lunch most Saturdays at the Southern Cross hotel in Potts Point with a few other close friends from ATN: Terry Pritchard, who was involved in marketing, a job he’d later take on at MGM in London; my occasional secretary Wendy Hunter, also on the production team at 7; Patti Mostyn was Johnny O’Keefe’s assistant at the time and went on to be a major international force in PR; Jimmy Fishburn, producer of the early Bramston shows. And Michael. It was an hour in which we could all let off steam and relax after the gruelling week of rehearsals.”

Gordon Chater said Plant “had wit, an unbiased and searching mind, a creative pen, and an interest in life, which ranged over everything from sport to religion, from theatre to politics. He also had a remarkable power of decision-making, something which he may have inherited from his father, a former general. He had tact and diplomacy. And he worked harder than anyone I knew.”

Perhaps too hard. Plant was putting in over 80 hours a week on The Mavis Bramston Show, and somehow had also found time to co-write a book, In and Out.

Creyton: “The Saturday before he died, we all lunched as usual. Thinking back, there was no real indication Michael was overly depressed. His partner of some years had died in an accident playing football just a short time before, and while that was a cloud, it was not one that seemed to obtrude on his friendships or his job. He left us early that Saturday to get on with work. He left with a cheery goodbye and said he would see me Monday at rehearsal.”

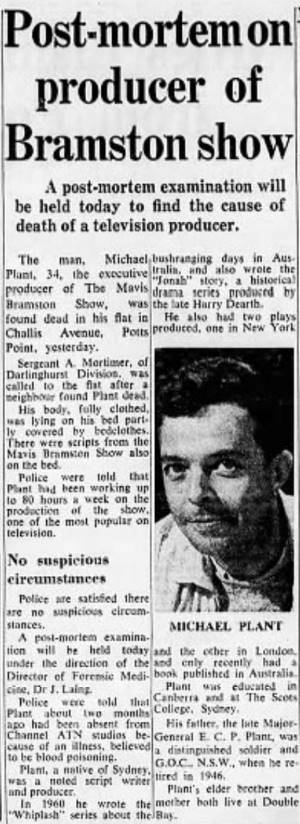

On

Monday 12 July 1965, Plant’s neighbour entered the Potts Point

apartment and discovered Michael Plant lying dead on his bed, fully

clothed, with scripts for The Mavis Bramston Show scattered around him. Police said there were no suspicious circumstances – the death was ruled to be caused by an accidental drug overdose. Most contemporary reports said he was 34 years old; going off the date of birth on his imdb page, he was 35. He was survived by his mother Oona (who would die in 1967) and brother.

On

Monday 12 July 1965, Plant’s neighbour entered the Potts Point

apartment and discovered Michael Plant lying dead on his bed, fully

clothed, with scripts for The Mavis Bramston Show scattered around him. Police said there were no suspicious circumstances – the death was ruled to be caused by an accidental drug overdose. Most contemporary reports said he was 34 years old; going off the date of birth on his imdb page, he was 35. He was survived by his mother Oona (who would die in 1967) and brother.

Barry Creyton: “I have a vivid memory of the day I was told of Michael’s death. It was at a rehearsal for the Bramston Show.”

“I walked into the rehearsal hall in Eastwood to a room full of solemn faces. Carol hurried to me before anyone else could speak and, very gently, gave me the news. At twenty-five, I’d never really encountered death as something personal, of someone close to me, and I was in shock for most of that day. Ultimately, Gordon with his usual practical attitude, insisted we get on with rehearsal as Michael would have wanted.

“There was rumour at the time that Michael took his own life, but I doubt that was the case. There was certainly no indication at that last luncheon.”

The Bulletin said on his death that Plant “had left as big an impression on Australian viewing habits as any one man in the industry’s brief history.”

Barry Creyton: “His impact on Australian television cannot be underestimated. It was his energy, his knowledge, his wit, his expertise that moulded what was, at the outset, an idea to emulate the British That Was The Week That Was, into something distinctly Australian. The Mavis Bramston Show was a sensation thanks to his boldness of approach. He was trusted implicitly by the execs at ATN and given free rein simply because his track record was so remarkable.

“To this day, I lament his loss to the business, and as a friend who guided me through some tricky times in my life both private and public. “

Michael Plant’s career was truly comet-like. An industry professional by the age of 19, a veteran of London, New York and Hollywood by the time he was 30, dead by the age of 35. He had a play on Broadway, TV credits in the US, England and Australia, and was head of the show that revolutionised Australian television. And he never saw 36. It was a remarkable life, awe-inspiring in its achievement, tragic in its brevity.

The author would like to thank Barry Creyton and Noeline Brown for their considerable contributions to this article.

Ralph Peterson papers

Ralph Peterson papers