An early Australian TV series. It was sponsored by BP and made with the co operation of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and the Victorian Civil Ambulance Service.

Best source is this profile here at Classic Australian Television here. See TV Week on its cancellation below.

Roland Strong wrote it. BP/Cor sponsored it. Contract was for 52 episodes. It went for sixteen episodes.

Premise

Hospital drama.

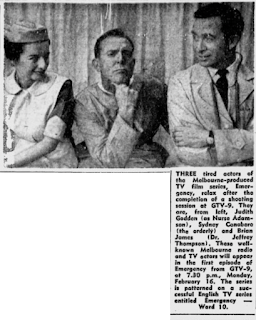

Cast* Brian James as Dr. Geoffrey Thompson

* Syd Conabere as orderly George Rogers, Thompson’s trusted assistant

* Judith Godden as Nurse Jill Adamson - she has biographical info here, here and here. She was a child actor.

* Moira Carleton as Matron Evans

* Natalie Raine as played May, the hospital switchboard girl

* Nevil Thurgood an Ambulance officer.

Production

It was announced in November 1958.

Filming began January 1959.

GTV sent a programme executive to London to learn about the production methods on the British series, Emergency – Ward 10 and a large set was constructed in GTV’s Studio One, the same studio where the variety programme In Melbourne Tonight was recorded. The Emergency team had to vacate the studio by 6:00 PM so that the huge set could be removed to allow the IMT set to be moved in, ready for rehearsals at 7:00 PM.

The Royal Melbourne Hospital loaned various medical equipment items

and provided training for the actors in its usage. The Victorian Civil

Ambulance Service supplied an ambulance and an ambulance officer.

The show was recorded on kinescope (videotape was not available at

that time), and each half of each episode (there was a commercial break

at the halfway mark) had to be shot continuously with no breaks. If an

actor fluffed a line or missed a cue, or a set shook, the scene could

not be re-shot. This inability to remove errors from the finished

episode was one of the primary criticisms of the series.

From the Classic Australian TV site:

From the start, Emergency had more than its fair share of problems. The programme was recorded on kinescope, as videotape was not available at that time, and kinescope was the only process available to record television images on 16mm film. (A special 16mm camera was focused on a high intensity screen and the pull-down was synchronised to occur during the second frame of the interface). While this process had the advantage of speed - each scene could be viewed as it would appear on screen, without having to wait for film rushes to be developed - it also had one serious drawback. GTV-9 management decreed that a sliced film could not be telecast, therefore each 13˝ minute block had to be recorded in its entirety (the programme had a centre commercial break). If an actor had trouble with a line of dialogue, or a set shook, the scene could not be re-shot. This inability to remove errors from the finished episode was one of the primary sources of criticism for the series. As reviewers commented, viewers don't expect to see actors stumble on lines in a filmed show.

Another source of criticism was the quality of the scripts. Because the top scriptwriters in Melbourne at the time did not want to be involved with the project (most thinking that Emergency, with its limited facilities, had no future), Roland Strong was forced to write many of the scripts himself. Strong's wealth of experience as a top radio scriptwriter (notably on Crawford's landmark series D24) should have guaranteed quality scripts. It didn’t. The episodes were still being written largely as radio scripts, without sufficient allowance for the visual impact of television. For example, viewers would see a patient in a bad way in a hospital bed, with the doctor nodding grimly and saying, "Yes, he's very sick" - something immediately obvious. Some segments were, in effect, 'radio with pictures'.

Roland Strong probably wrote more than half of the scripts, however in later stages this task was shared with GTV programme executive Denzil Howson. They both wrote under various pseudonyms because the General Manager of GTV-9, Colin Bednall, thought it was blatant nepotism for all the scripts to be written by the same two GTV people. Therefore a number of fictitious writers were credited, and Bednall was never aware of the deception.

Emergency did have several points in its favour - an excellent performance by Brian James in the lead role, a solid supporting cast and generally good sets. The audio crew of Wally Shaw, John Cannon and Rex Israel worked wonders with sound, hiding microphones in bed-pans, under pillows and behind vases of flowers, and inserting recorded music bridges ‘on the run’ - there was no post-editing.

Emergency also featured brief filmed sequences on location in some episodes, shot by a Movietone News cameraman on 35mm to ensure maximum quality when transferred to kinescope. It must be remembered that Emergency was one of Australia’s first drama series, and very much a pioneer effort. Regular production of Australian drama series did not come about until 1964 with Homicide, by which time video tape was available for studio scenes, with outside location work being shot on film. The early episodes of Emergency rated fairly well and, given time, the production difficulties could have been sorted out.

The demise of Emergency, however, was due almost entirely to a scathing attack made on it by a Sydney daily newspaper, which ran a half-page article ridiculing the series. So vicious was the article that BP/COR executives called a crisis meeting with GTV management, and announced they were withdrawing their sponsorship. GTV was unwilling to absorb the production costs alone, and as the Emergency set took up space which could be used for more profitable variety programmes such as In Melbourne Tonight, production was halted after the 16th episode.

While Emergency was as good a first attempt at drama as could be expected, it would be a further five years before GTV-9 would make it’s next venture into in-house production with the situation comedy Barley Charlie. From that point on, drama series produced at GTV would be packaged by independent producers, such as Hunter and Division 4 from Crawfords. Only six complete episodes of Emergency are known to exist, and it is extremely doubtful that any others have survived.

1. (Title unknown) - 16 Feb 1959 (Melb), 23 Feb 1959 (Syd)

Mr. Green.......Frank Gatcliffe

Mrs. Green.......Joyce Turner

Shirley Green.......Diane Sinnamon

May.......Natalie Raine

Ambulance officer.......Nevil Thurgood

Synopsis: A car crashes through a safety fence and rolls down a hillside in Fern Tree Gully. Two injured passengers, a man and wife, are taken to hospital, where they regain consciousness and ask for their daughter, who was also in the car. A search party is sent back to the accident site to find the missing child. Pictures are here

2. (Title unknown) - 23 Feb 1959 (Melb), 2 March 1959 (Syd) Script.......Roland Strong

Miss Marshall.......Patricia Kennedy

Mrs. Marshall.......Lorna Forbes

Watkins.......Paul Bacon

Miss Marshall's friend.......Madeline Herle

Matron Evans.......Moira Carleton

May.......Natalie Raine

Synopsis: A stubborn daughter is convinced that her mother, suffering from a serious disease but gradually recovering, would receive better care in a private hospital. Dr. Thompson and the matron realise that the 'hospital' is run by a 'quack', and strongly advise the woman to let her mother remain where she is. The daughter refuses and places her mother in the care of the 'quack' whose 'miracle cure' consists mainly of starving his patients. When her mother becomes weak and dangerously ill, she rushes her back to the Emergency Ward, but she is beyond help and dies shortly after.

3. Blackout (2 March 1959 - Melb), 9 March 1959 (Syd)

Girl.......Golda Prince

Synopsis: A lost and frightened girl arrives by train in Melbourne and a kindly policeman takes her to hospital. Her memory is gone, but kind and persistent treatment by the team in the Emergency Ward restores both her memory and her happiness.

4. Lethal Bag - 9 March 1959 (Melb), 16 March 1959 (Syd)

.......Peter Aanensen, Philip Jordan, Kenneth Jackson

Synopsis: Dr. Thompson's car is stolen and wrecked by thieves. Two small boys play among the wreckage and later leave with Dr. Thompson's medical bag, which contains dangerous drugs. There follows a frantic race against time to locate the children, one of whom has forced the other to swallow some of the drugs.

5. Gunshot - 16 March 1959 (Melb), 23 March 1959 (Syd)

Edna Remington.......Anne Harvey

Synopsis: Edna Remington, associate of criminals, is shot and taken to hospital. The criminals, however, are desperate to silence her, and break into the hospital. Threats are made to the hospital staff - if the lady lives lives, they will pay.

6. (Title unknown) 23 March 1959 (Melb), 30 March 1959 (Syd)

West.......John Morgan Script.......Denzil Howson

Synopsis: A man is knocked down by a car and brought to hospital, and after treatment he is discharged. Soon afterwards he returns to the hospital in mysterious circumstances, and Dr. Thompson and George Rogers are faced with a possible suicide attempt.

Notes: Script is credited to Graeme Herbert, a pseudonym for Denzil Howson. A complete copy of this episode is held by the National Film & Sound Archive.

7. Operate Remote - 30 March 1959 (Mel), 6 April 1959 (Syd)

Synopsis: A man is badly injured in an accident on a country road and bleeding from a severed artery. He is saved through the use of a taxi's radio when Dr. Thompson relays instructions to the driver. Matters are complicated by a criminal and his girlfriend.

8. Knockout - 6 April 1959 (Melb), 13 April 1959 (Syd) - another source says this ep was 23 Feb (Melb) - confirmed here

Girlfriend.......Judith Thompson

Mick Fenton.......John Godfrey

Synopsis: Boxer Mick Fenton is threatened unless he 'throws' an important match. Fenton also risks losing his eyesight if struck in the head; his girlfriend knows this, and says she will leave if he fights. He fights, wins the bout, and is viciously bashed on his way home. An emergency operation is performed, his eyesight hanging in the balance.

9. Death Drive 13 April 1959 (Melb), 20 April 1959 (Syd)

.......Edward Howell

Synopsis: Two reckless teenage boys are involved in a car accident, and later involve their parents in a tangled web of consequences.

10. Alibi. 20 April 1959 (Melb), 27 April 1959 (Syd)

Synopsis: A young man commits a robbery, and attempts to create an alibi for himself by slashing himself with a broken bottle - but fate intervenes.

11. False Alarm - 27 April 1959 (Melb) 4 May 1959 (Syd)

.......Bruce Wishart, .......Margaret Reid

Synopsis: Young Bobby Farrel rings the police for a joke and reports a bogus bus crash involving 30 people. Dr. Thompson, en route to visit the boy's mother, is diverted to the hospital in readiness to tend to the accident victims. Meanwhile, the mother's sudden fainting turn at home causes her to collapse beside her stove's leaking gas jet.

12. '44 Incident aka Anzac Day - 4 May 1959 (Melb), 11 May 1959 (Syd)

Phillip Bateson.......Ron Pinnell

Mrs. Lewis.......Marjorie White

Detective.......John Hughes

Ambulance officer.......Nevil Thurgood

Synopsis: During the Anzac Day march, one of the men marching collapses and is taken to the hospital, where he is recognised by George Rogers as a man who served in Italy during World War 2 and deserted following the suspicious death of another soldier.

13. Diamonds For Leona - 11 May 1959 (Melb) , 18 May 1959 (Syd)

Leona.......Marcella Burgoyne

.......Noel Ferrier

.......Clive Winmill

Synopsis: A jeweller's apprentice learns that the girl he loves is using him to gain information for a jewel robbery. He is later stabbed in a fight with her accomplice, but manages to board a bus and reach the hospital.

14. Talent Quest - 18 May 1959 (Melb), 25 May 1959 (Syd)

Synopsis: An ambitious mother of a little girl wants her to be a stage star, entering her in competitions and overworking her to the point of collapse. The mother then starts using 'pep pills' to keep her going. Finally, the child collapses and is rushed to hospital.

15. Mind Over Matter 25 May 1959 (Melb), 1 June 1959 (Syd) Script.......Denzil Howson

Petula Rogers.......Sheila Florance

Amelia Stephens.......Eve Wynne

John Hartley.......Williams Lloyd

Elizabeth.......Judith George

Ambulance officer.......Nevil Thurgood

May.......Natalie Raine

Synopsis: After having been led to believe, by malicious gossip, that she is dying from cancer, a distraught woman attempts to kill herself.

Notes: Originally scheduled for 23/3/59, as episode 6.

16. Broken Appointment - 1 June 1959 (Melb), 8 June (Syd)

.......Kenric Hudson

Synopsis: A young man determines to marry the girl of his choice, in spite of his parents wishes. On his way to visit her, he is involved in an accident and rushed to hospital. His girlfriend, thinking he has deserted her, takes an overdose of sleeping tablets and is also rushed to hospital. Eventually she and her boyfriend are happily reunited.